I hereby proclaim that; there are ONLY 10 different ways a decision can be made!

At least in a meeting with several participants.

Sorry for starting with this click baity statement. On the other hand – I haven’t been disproven so far. Regardless of if this is true or not, I believe that the art and skill of decision-making is an increasingly important topic. Why do I believe that?

In many organizations, I often encounter the assumption that a decision is either made by one person, or by a group that has discussed a proposal until everyone agrees. If this is actually true, your ability to conduct effective, efficient and inclusive decision-making is sadly limited. A rapidly increasing number of companies go agile, organizing people into a network of autonomous teams, supported by teams of managers and leaders.

Decision-making and ownership are decentralized to those closest to the problems and opportunities. Leadership is no longer manifested in hierarchies of individual accountability, but in interconnected layers of supportive leadership teams. Just as agile teams collaborate to delivering value to users and customers, so must the leadership collaborate when working, meeting and making decisions. A leadership team’s ability to reach a shared understanding through debates and discussions, explore options and then together decide on the best path forward – is crucial. The speed to decision and time to review and evaluate the impact will dictate your whole organization’s ability to quickly respond, learn, adapt and improve.

With this blog I hope to expand your toolbox and inspire you to experiment with a more varied approach to decision-making.

.

Book: Decision-Making Principles & Practices

If you and your management team want to become better at having efficient meetings with effective decision-making, you might want to read more about decision-making principles and practices in my new book.

The title of the book is “Toolbox for the agile leadership team – 27 Decision-Making Principles & Practices (How to reach strong inclusive agreements with consent)”.

The digital version is available on LeanPub and you can buy a physical copy on Amazon.

.

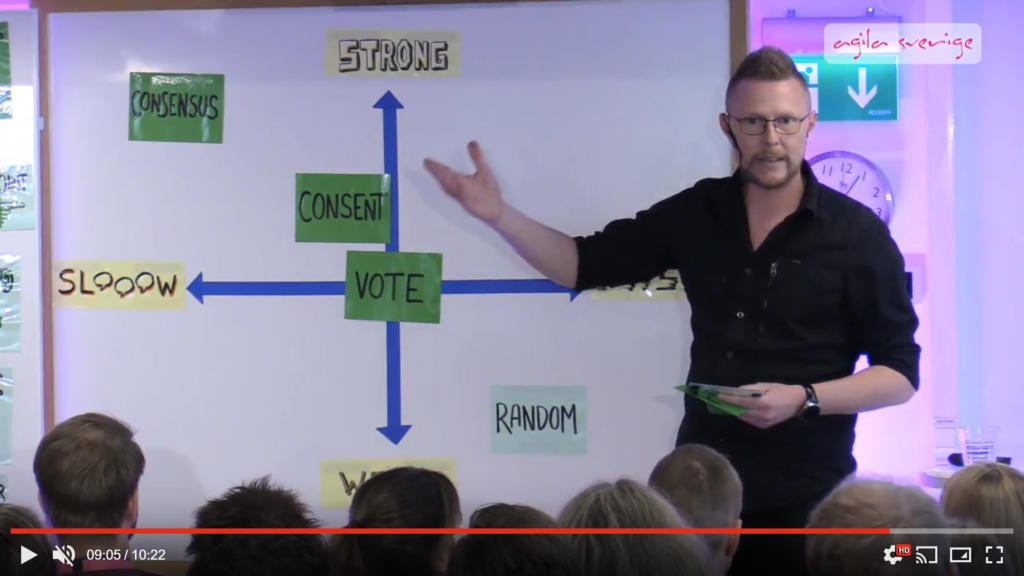

Video (in Swedish)

I recently gave a 10-minute lightning talk on this very subject at Agila Sverige 2019. If you don’t speak Swedish, perhaps skip the video and continue reading my summary of the talk below.

https://agilasverige.solidtango.com/video/there-are-only-10-different-ways-a-decision-can-be-made

.

The 10 different ways a decision can be made

I argue that when a decision has been made by a group, it can be derived from one of the following categories:

1) Vote

People or subgroups present different proposals. The participants then Vote. The most popular proposal “wins”. If there is a tie, you can choose to decide with the toss of a coin. This approach ensures that a decision is actually made.

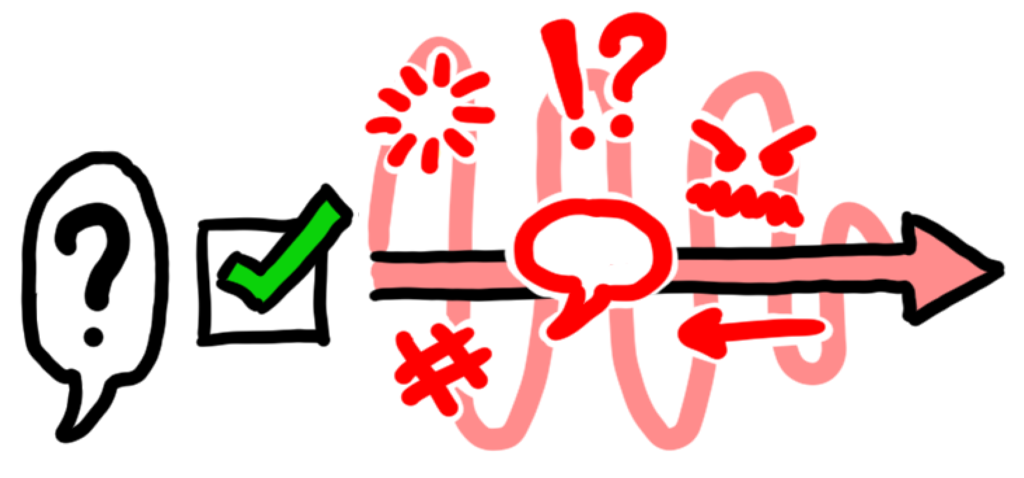

However, the approach comes with some drawbacks. What usually happens is that the advocates for the different proposals dig opinion trenches. They spend energy arguing the benefits of their own proposals and convincing the group of the problems/risks with the other proposals. Instead, that energy could be invested in understanding each other, which might lead to a shared “reality” and a joint path forward. Furthermore, the “losers” might not be committed to the outcome. They might even work against it, undermining its success or impact.

2) Consensus

The group collaborates on a proposal until everyone agrees that this is the best path forward. If successful, this creates a very strong outcome. Everyone feels included in the dialog that shaped the proposal and feel committed to executing on the decision or honouring the new policy. However, this might consume a lot of energy. Arguing, listening, explaining, debating and reaching a shared understanding and collaboratively design a proposal everyone approves – can take a lot of time.

3) Consent

Someone (or a subgroup) presents a proposal. Unless there is a qualified objection, the proposal is accepted and decided upon. If there are objections, these are valued since they are used to collaboratively further improve the proposal.

When deciding through Consensus, you can block a proposal if it doesn’t feel right. When using Consent, this isn’t good enough. For an objection to be qualified you need to be able to explain why it would be bad for the team, project or the company, and be able to present an idea on how to improve the proposal itself.

4) Power

The decision is made by a single person who believes they have a mandate to do so. The authority to decide can be derived from a formal title, seniority or role. The person making the decision might ask for advice or feedback and then base the decision on data and research – but the decision is ultimately done by him/her. Agreeing with oneself is fast, and it’s usually very easy to invent a rationale behind the decision in hindsight.

Delegate – Appoint

One way to delegate to a person or a smaller group, is to appoint them. But for one person to feel that they have the mandate to appoint someone else, that person needs to believe that he or she has enough authority to do so. That’s why I don’t regard appoint as a decision-making technique in itself but categorize it in under Power. The pros of appointing someone is that you ensure someone will do it. The obvious con is that the person might feel forced, thus reducing commitment and ambition to do a good job.

5) Random

Some decisions we actually allow chance to make for us, especially if they are safe and risk free. We might decide who starts presenting by spinning a pen. Choose teams for the charade championship by pulling names from a hat. But sometimes we also use chance for more serious situations, such as when we have a tie when voting and we need to have a “winning” option.

6) Algorithm

Some decisions aren’t made by people but by an agreed upon algorithm. Deciding who is responsible for facilitating the next retrospective could rotated in the team with a list of names guiding the rotation. The backlog could be strictly ordered using cost of delay weighted against work effort (or story points). I even know of companies who have eliminated negotiation from the salary review process. Instead your salary is dictated by a set of input parameters (years at the company, graduation degree, etc) and an algorithm.

Once we have an algorithm, the decision can be made super fast. But how do we define the algorithm? By consensus, consent or voting? Or is it dictated by someone with power?

7) Delegate – Volunteer

Another approach to delegate work and decision power is to ask for volunteers. Whoever raises their hand gets to carry out the responsibility.

As all approaches, this comes this pros and cons. Let’s start with pros. The volunteer is probably passionate about the task and will make sure to do a great job since he/she took it on voluntarily. On the other hand, the person might “take one for the team”, not really wanting to carry out the task. If this happens repeatedly, i.e. the same person always volunteers, you might risk having martyrdom behaviors. Another risk is that the volunteer, although he/she has the passion, doesn’t actually have the skills to do the task sufficiently. But then again, what is most important? Drive and motivation or skills? Do we value growth over skill optimization?

And then we have another question; what do we do if we have too many volunteers? Or none at all?

8) Delegate – Nominate

A third way of delegating work and decision power is through nomination. First you discuss the expectations on a person taking on the task and the extent of included decision power. Then the group nominates someone they believe would be a great fit for responsibility.

The details of how people are nominated and who is chosen can vary and need to be established before the nomination process starts. One benefit of this approach is that the person elected has the trust and support of the whole group.

One drawback could be that the nominated person feels “forced” to take on something he/she doesn’t want to do. It might not be easy to turn down a nomination (even though it’s indeed allowed) when the whole group tries to convince you that you will do great.

Another risk is that the person isn’t “qualified”. But I’m not so concerned about this one. I’ve seen people risen to the occasion when given the opportunity to accept responsibility, especially when encouraged and supported by their peers.

9) Emergent

Sometimes we can’t back trace a policy or rule to a specific decision. Imagine this: Stephanie makes an impulsive decision (without consulting anyone) to do X in the midst of an urgent stressful situation. It works out. Some time later Stefan encounters a similar situation, remembers that someone did something, and does the same. It works out this time as well. Slowly this seeps into the library of “this is how we do things around here”, maybe even sneaking it’s way into the intranet or wiki. No conscious decision was ever made by a group, but still it somehow developed into a rule or policy. When asked why, people have a hard time to retrace the reason or for how long this has been a rule.

There are no pros and cons about this, it’s just the way habits and culture evolve at a workplace. Without this collective behaviour we wouldn’t survive. Each micro decision would take forever. But, of course we should be allowed to scrutinize and criticize these unconsciously emergent decisions, talk about them, and maybe establish new, more thoroughly thought through decisions. “This is the way we do things around here” should never be a valid argument to fence off certain topics from discussions.

10) Status Quo

Actively deciding not to change things, to accept the Status Quo, is a perfectly valid discussion outcome. However, to clarify what Status Quo means often helps the group muster up the energy needed to discuss things through to a point where a decision can be made, thus introducing a change for the better.

.

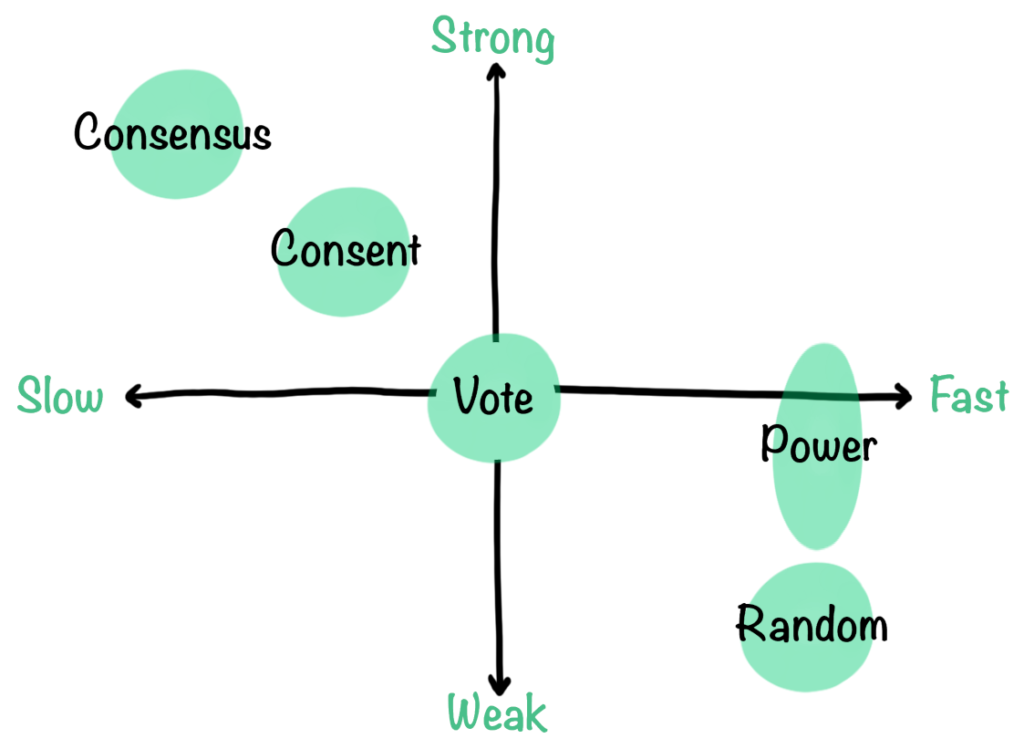

Speed and Strength of decisions

As you’ve probably already realised when reading the list above, some ways to decide are fast, while others take a lot of time and energy. Some ways result in strong outcomes (people feel included, committed, that the decision is a win-win, etc.), some in weak outcomes (some people feel excluded, like “losers”, or not committed).

In the graph below I’ve plotted how I believe the different decision-making approaches relate to each other.

Some comments:

Algorithm – Once the algorithm is in place, it’s instantaneous. But it can take a long time to decide on the algorithm, especially if decided with Consensus.

Volunteer/Nominate – If the delegated work and responsibility is given to a group, that group in turn need to figure out how they want to make decisions. This is why these aren’t included in the graph above.

Emergent – Not sure where to put this. Maybe slow and strong…

.

Summary

Being aware of the different ways decisions can be made will hopefully make you more conscious when deciding upon decision making principles. Giving this set of questions, do we want to optimize for speed or inclusiveness, making any decision over making the right decision, etc. Naively assuming you have to choose between “the boss decides” or “everyone has to agree” severely limits your options.

Some critical situations require fast decisions made by a single person. But when you understand the potential risk and cost you might consider another path for some situations. The energy “saved” from debates might have to be repaid afterwards when you need to defend or justify the decision, sell it to sceptics and create buy-in, monitor and follow up that the decision is honored.

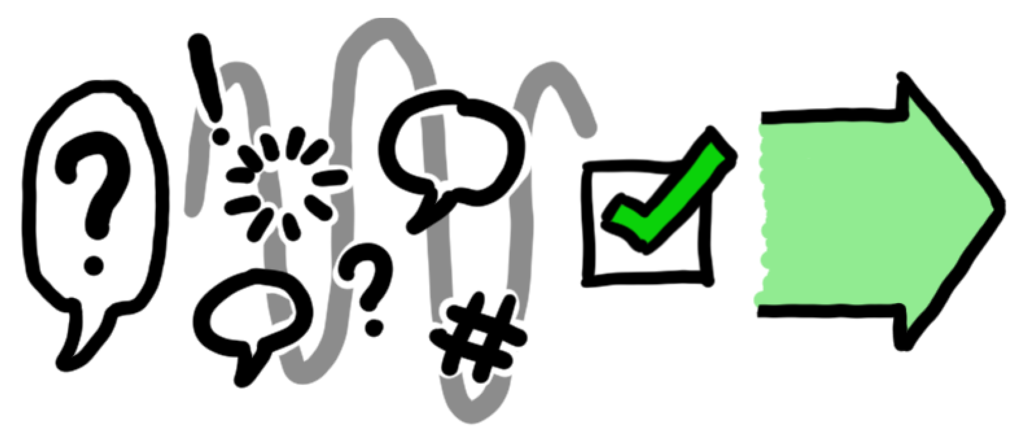

But most often that’s not the situation. The topic is important, but nothing is on fire. By allowing time for debates, discussions, alignment of values, etc, the decision (once it’s made) will be far stronger. People involved will be committed, understand why the decision was made and be motivated to make it work.

Do you agree with the list? Have I missed a decision-making practice? Which is the most common ways to make decisions in your team and company?

Jag tror du måste ändra lite i definitionen av “Power”, eftersom det inte måste vara bara en person, utan en formell eller ad-hoc grupp som bestämmer genom Power över en större grupp.

congrats very synthetic and effective exercice (again) !