If the acronym VUCA hasn’t made sense so far, then in these pandemic Covid-19 times it surely must. The acronym stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. So when people refer to a VUCA world, they refer to a world where you cannot possibly foresee everything ahead of time (if anything, really). This is true to the whole world – the planet Earth, but also to the world, or context if you like, in which you and your organization operate.

The world does not need a pandemic to become “VUCA”. Before the outbreak of Covid-19, the fact that your organization was already in a VUCA world was true. Deregulations, globalization, knowledge work, the Internet, increased pace in almost everything, etc. made it so. I listened to a global CTO of a Telco roughly 6 months ago who said that every step in their value chain was being disrupted. Now, with the help of the Internet and the digitization of everything, the competition can come from anywhere at any time.

Simplifying change

Just reflecting on how hard it is to change your own behaviours, imagine trying to change the behaviours of hundreds, thousands or even tens of thousands of people! It is an extremely complex endeavor. And what happens when we consider something being extremely complex? We try to simplify it, make abstractions, create models, frameworks, and make generalizations in order to try to make sense of the work at hand.

There is of course a multitude of models for driving change. Kotter’s eight step model, ADKAR, McKinsey’s 7S, Lewin’s 3 steps, etc. They prescribe steps to be taken to drive change. Great, just follow the steps and we will be done! Go make it so!

And off we go. And sooner or later we run into problems, simply because the work is more complex than what a step-by-step model can handle.

Driving organizational change in a linear fashion simply does not work.

The most common mistake is to take these models literally and work in a linear fashion. After all, it’s called Kotter’s 8 steps, right? You take one step after another, yes? No.

I cannot stress this enough. Driving organizational change in a linear fashion with a faster-changing world simply does not work. As John P. Kotter himself says about the 8-step model – “But that methodology has a hard time producing excellent results in a faster-changing world.” (from the November 2012 issue of Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2012/11/accelerate).

What to do?

“The only constant in life is change” (Heraclitus, Greek philosopher, 535 BC – 475 BC)

No matter if you are doing a full blown agile transformation, a digital transformation, or really any type of transformation to your organization, we have to accept that we cannot keep up with the pace of change.

Using John P. Kotter’s own words again; “I could give you 100 examples of companies that, like Borders and RIM, recognized the need for a big strategic move but couldn’t pull themselves together to make it and ended up sitting by as nimbler competitors ate their lunch. The examples always play out the same way: An organization that’s facing a real threat or eyeing a new opportunity tries—and fails—to cram through some sort of major transformation using a change process that worked in the past.” (from the November 2012 issue of Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2012/11/accelerate).

It is time to use methods that take into account that we cannot foresee everything, that we need to work at many levels at the same time, that people handle change in different ways and that what worked with one group of people might not work the next. I am personally inspired by Lean Change (by Jason Little, https://leanchange.org/) and Kotter’s Accelerate.

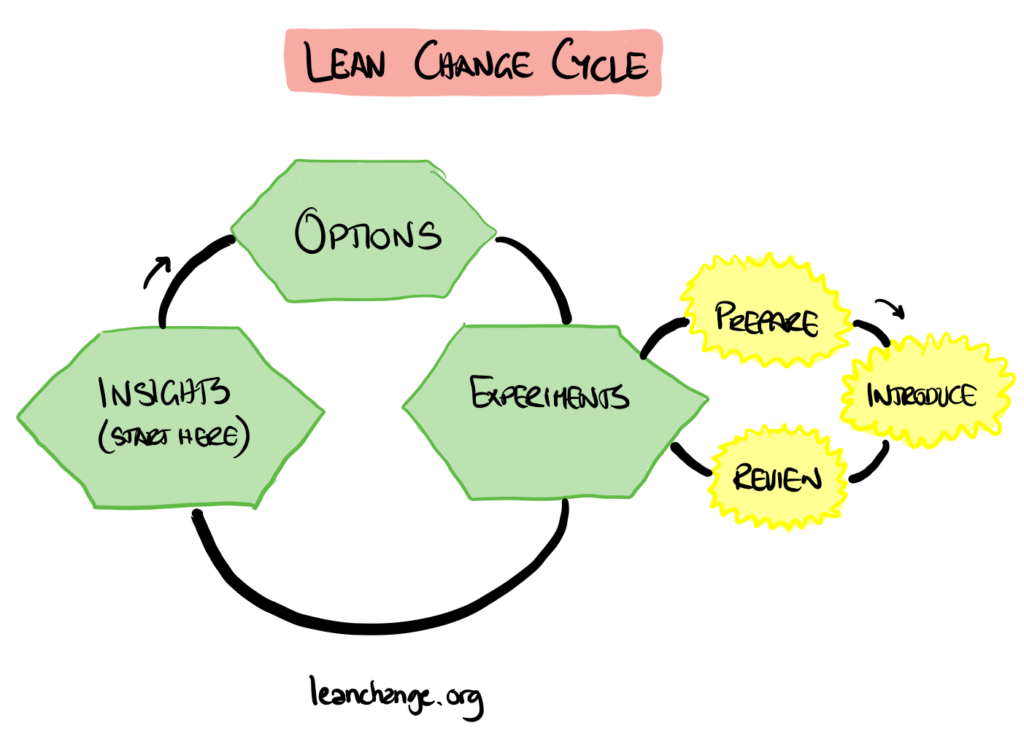

Lean Change has a feedback based, iterative approach to change management that makes a lot of sense in a complex situation. By finding data, we can get insights into how the situation is today (compare with sense of urgency from Kotter). These insights lead to a number of options you can act upon. By evaluating the options, you choose something to do. You begin with formulating that as an experiment with a hypothesis. You then prepare, introduce and when done, evaluate the results from the experiment. The results will then feed more insights, that will give you new options. So based on the feedback, you iterate. The beauty here is that the model doesn’t prescribe what you should do, but rather gives you the opportunity to find your own way given your unique context.

An Example

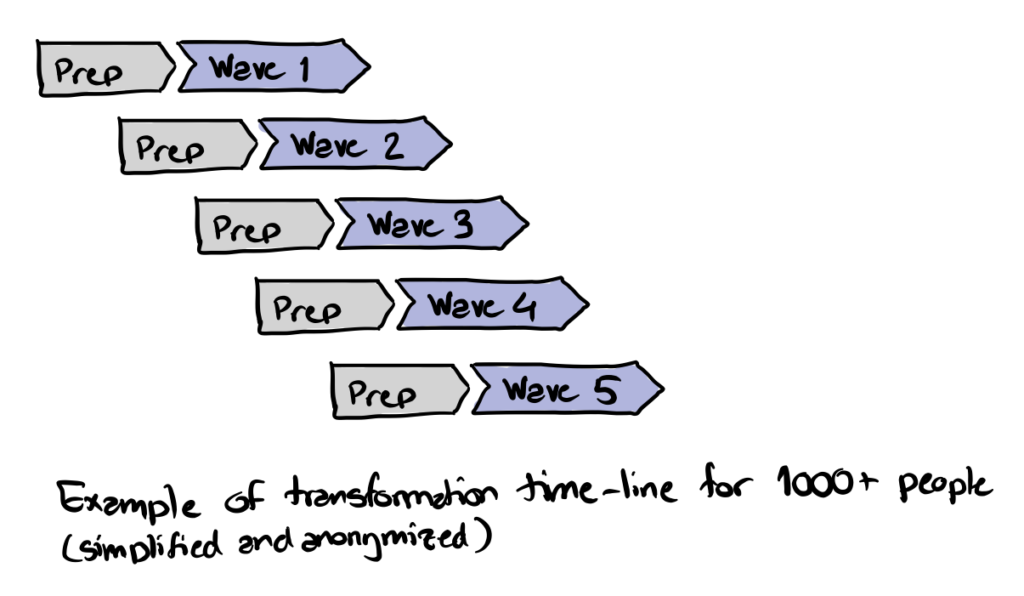

At a recent assignment, I was tasked with starting up change in a division of the company, consisting of 6 departments. As the rest of the company was going agile, this division realized the benefits and wanted to change as well.

We created a group of people from each department that was interested in doing and driving this change (a guiding coalition from Kotter’s 8 steps to change, if you like). This group had the full support from the division’s management.

Among the many things we did, we also gathered data. Employee engagement surveys, different metrics, other forums that had focused on collecting problems, etc. And to no surprise, the main insight was that the departments had different needs! For instance, one department handled mainly operational support, and the support functions were knee-deep in different ITIL processes. There was a need to simplify, but to go full blown Agile Manifesto type of agile seemed not to fit. Whereas another department mainly consisted of developing stuff. The insight here was that creating cross-functional teams would make more sense. At a third department the mere word “agile” made people frown and say things like “that’s only for software development”. The insight here was that we needed to be careful with our wording. So we conducted an experiment where one bigger task that required some 10 people was changed into sprints, with plannings and sprint reviews. This without using words like “sprint” or saying that it was “agile”. Our hypothesis was that if they just tried this way of working, they would like it.

Now, the point is this. If we would have made a linear plan for all departments (perhaps starting with training, then creating cross functional teams, and then adding some agile coaches and get going) it would have failed at two of these three departments.

In a nutshell; you need to have an agile approach to become agile!